For the past few years, right-wing media have argued that the U.S. is plagued by a masculinity crisis, whether it’s former Fox News anchor Tucker Carlson warning of collapsing testosterone levels in his 2022 documentary “The End of Men” or Sen. Josh Hawley decrying what he called the left’s project to “deconstruct” men and “define traditional masculinity as toxic.”

Rhetoric aside, there may be a real vein that these pundits and politicians are tapping into.

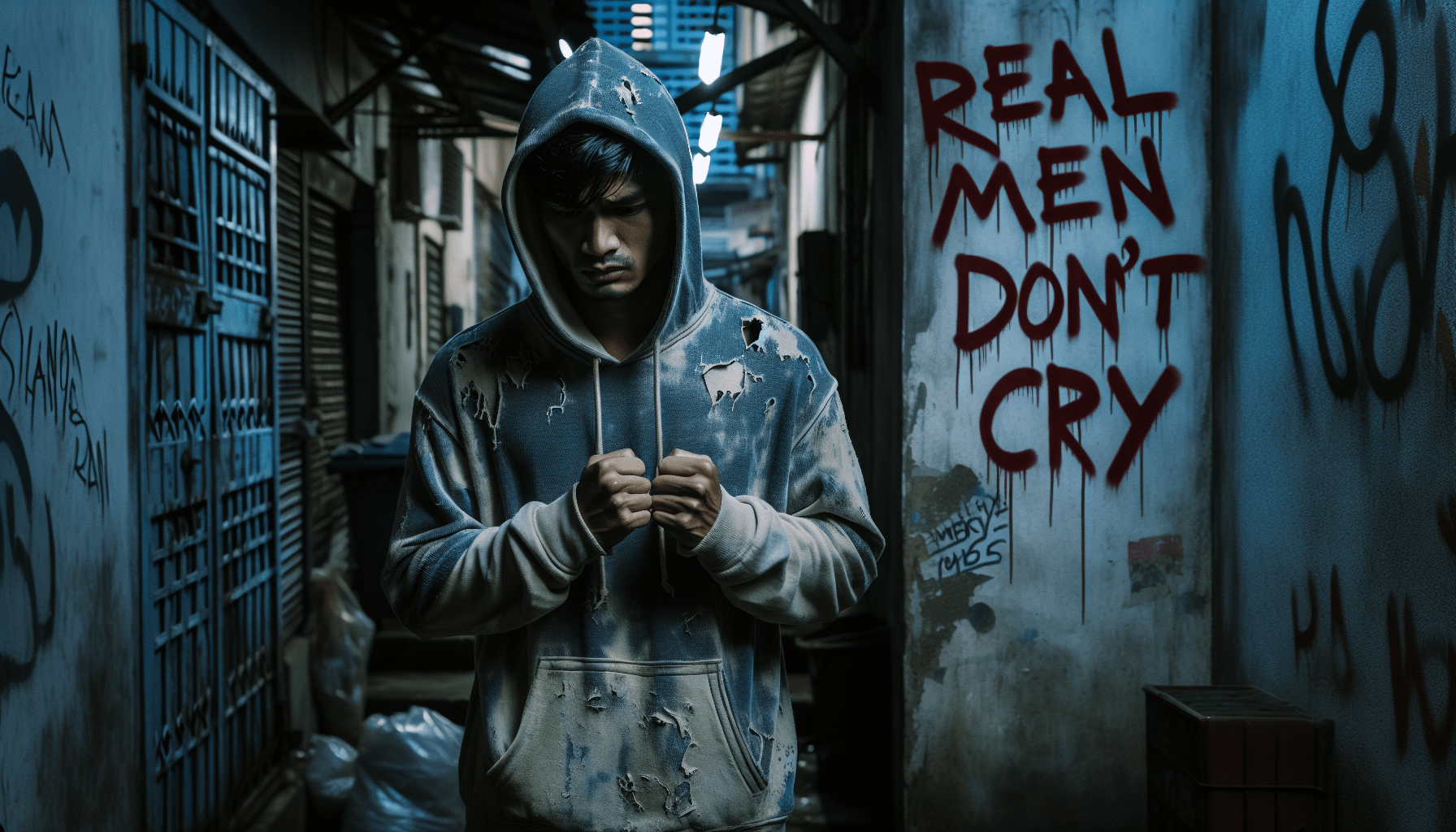

Deaths of despair, which are caused by drugs, alcohol or suicide, are disproportionately experienced by men. Meanwhile, many of the traditional markers of manhood – earning enough money to raise a family, buy a home or even rent an apartment – are becoming increasingly difficult to obtain.

What does it mean for society if young men sense that their masculinity is under threat? Or for our politics if young men see less hope for the future?

In 2021, psychologist Adam Stanaland and his colleagues conducted an experiment exploring masculinity anxiety in young men between the ages of 18 and 40. They found that statements as simple as “you are less masculine than the average man” could provoke aggression among the study’s participants.

For their next study, they turned to adolescent boys, with a couple of key questions in mind: When does masculine anxiety start to appear? And what fuels it?

In the findings, which they published in July 2024, they were able to show that boys in late puberty – but not those in early puberty – would respond aggressively when their masculinity was challenged.

Not all boys in late puberty reacted this way; those most prone to aggression tended to care a lot about what other people thought about them. Their parents were more likely to have lower incomes, less formal education and associate masculinity with traits such as power and dominance. They were also much more likely to live in counties that supported Donald Trump in 2020.

In an interview, which has been edited for length and clarity, Stanaland discusses some of the broader economic and social forces that may have influenced his team’s findings and explores how they relate to the results of the 2024 election.

In your more recent study, you broke your adolescent participants down into two groups. There was this early puberty group and a late puberty group. And you found that the threats to masculinity only really started to have an effect in that later puberty group. Can you talk about why that might have been the case?

In prior research, we had already detected a pattern: The pressure to act stereotypically masculine predicts aggression in young adult men in the U.S., particularly when they feel like their manhood is under threat.

So we started to wonder – OK, well, when does this pattern start? We thought about age. But age is somewhat of a rough predictor of development, right? It’s just a number. Although age corresponds with social changes, such as changing schools and navigating new social situations, boys go through puberty at different ages.

For example, changes in secondary sex characteristics, such as height, body type and voice – these are going to affect how other people treat you. As boys’ bodies start changing, there’s going to be much more of an expectation for them to act in stereotypically masculine ways, just like adult men do. There are also vast cognitive changes going on during this time. You’re able to grasp social pressures with much more nuance than you could before. And part of that is realizing, “Oh shoot, if I don’t defend my manhood, then I won’t have friends, I won’t fit in, my parents might disapprove.”

In our research, puberty captured these nuances better than age. Age did predict these things, but puberty was just a much stronger predictor.

How did you threaten the boys’ masculinity?

Half of the participants were threatened and the other half were not, at random. We had everyone take two quizzes: a “Boy Questions Quiz” and a “Girls Question Quiz.” For the half whose masculinity we threatened, we would tell them they did poorly on the guys quiz – “Well, you missed more questions than other guys usually do. Based on your quiz results, it seems like you’re more like the average girl than the average guy.”

This was age-adapted from past work on masculinity threats to adults, because we wanted to be able to build on those findings.

Then you used a word completion task – for example, having boys complete the fragment “GU_” – to indicate whether they responded aggressively to threats to their masculinity. Those who wrote “GUN” as opposed to, say, “GUM” were said to be reacting aggressively. How do you know that this task is connected to real-world aggression?

This measure has been used in seminal research on masculinity and aggression, so we wanted our findings to directly align with that work. That research and others have found that this task is associated with actual violent behavior.

However, we tried to be very careful to say that we weren’t measuring aggressive behavior. Think of cognition as a first step. People who are thinking aggressively are going to be more likely to act violently or aggressively. Not everyone who is thinking aggressively is going to act on it, but cognition can predict it.

This measure is also great because it’s implicit – our participants didn’t know that we were measuring aggression. They were simply given this word completion task, which we presented as a game, and how they performed indicated how aggressively they were thinking in the moment.

In the study, you found that parents’ beliefs were a strong predictor of whether their sons reported being pressured to be stereotypically masculine. Specifically, it was parents’ endorsement of hegemonic masculinity – what you define as the belief that men need to be powerful, gain status and have authority over women.

Yes. We asked boys to respond to statements like, “My parents would be upset if they saw me acting like a girl.” And we found that this fear of upsetting their parents indicated whether they would endorse statements such as, “I’m like other guys because I want other people to like me.”

We also found that a fear of upsetting peers could pressure certain boys to feel as if they needed to “act like a man.” We just didn’t have data from peers to look at. So we couldn’t really try to understand, within peer groups, what exactly was going on.

We did, however, have data from parents, including the types of beliefs about masculinity that they endorsed, as well as certain social and demographic variables reported by parents.

Two data points for the parents stood out to me. Having less income and less formal education – which is also tied to less income – strongly predicted whether they possessed beliefs about hegemonic masculinity. Do you see any connection between economic anxiety and masculine anxiety?

There’s research showing that people who are under more economic stress – who experience economic hardship – more readily cling to racial stereotypes. This work has argued that poverty leads to stereotyping because high-status people are motivated to maintain the status quo when they believe that their position in society is threatened. Or this could be an example of cognitive depletion: The greater your anxiety over paying the bills, the less you’re going to be able to ponder gender and race.

We observed that working-class parents – who, in our sample, happened to be mostly white – were more likely to endorse these rigid, masculine ideas, especially about men being strong, powerful and dominant over people of other genders. And they’re the ones whose sons reported the most pressure to be stereotypically masculine.

And I think economic anxiety and poverty are a key part of this story. In times of prosperity, or in societies that are more socialist in their orientation – where you’re guaranteed basic health care and education, for example – do men feel less pressure to be on top, because they feel more economically and socially secure? I don’t know. It’s an interesting avenue for future research, along with looking at these processes within specific racial or ethnic groups.

I know that voting-age men weren’t the subject of your most recent study, but I wonder about the political implications of masculine fragility as young people come of age. Trump picked up a larger percentage of male voters under 30 than any GOP candidate had since 2008. In what ways did you see Trump tap into masculine anxiety on the campaign trail?

I think we, in academia, expected Gen Z to really just go all in for Harris – even white men, like the ones in our sample. And it just doesn’t seem to be like that’s the case, especially among Gen Z white men who are working class.

You saw this play out when Trump appeared on several podcasts whose hosts lean into that strong, macho persona, especially in the weeks leading up to the election.

In our two studies, we found that pressures to be masculine can predict aggressive responses among boys in later adolescence and young men – times of their lives when they are really trying to figure out what kind of man they will be in their relationships, at work and in their day-to-day lives. Coupled with rising economic uncertainties, these celebrities and politicians can give these men an outlet to demonstrate their masculinity, burnish their status and make them feel like they belong.

So much status in our society is tied to wealth. Might teens and young men – who are at the bottom of the totem poll, in terms of wealth – be latching on to more visceral expressions of power and masculinity?

I think it’s all wrapped up in that. Men start experiencing these pressures to be the provider in their family, to get their relationships and careers going, to make their way up the ladder at work.

A lot of these goals are becoming more difficult to attain. And so what we’re seeing is that in order to gain that status – or even out of fear of losing that status if they have it – boys and men will go to great lengths. Obviously, aligning with people – celebrities, politicians, business leaders – who have those same values will become more enticing.

What are your thoughts about how much of an influence media consumption can have on the development of certain beliefs about masculinity?

We don’t have great measures of peers or other factors like that. But we do have this measure where we asked parents for their ZIP codes, and we mapped that to the proportion of support for Trump in 2020, so not this past election. And we saw that it wasn’t necessarily parents’ self-reported political identity – so how liberal or conservative they are – that predicted their masculinity beliefs. It was this county-level, community-level variable.

So if you think about that finding, you would imagine that it’s not just the “physical counties” that boys are in. Digital spaces – social media spaces that boys are living in – are probably having an effect, too.

Remember, during late puberty, teens are trying out different identities. For whatever reason, some of these more conservative online spaces have become really appealing to certain boys and men. There is definitely some important ongoing work in this area, specifically on the manosphere.

Is there anything else that you’d like to add?

These pressures to be stereotypically masculine come from parents, peers and the community. And they don’t seem to be changing or dissipating as quickly as we in academia thought they might.

For example, you might think of Gen Z as this liberal group that’s super into social justice. And that just doesn’t seem to be the case, especially among certain men and boys from working class backgrounds.

So I think we should be a lot more attuned to that lack of change – the social and economic sources of these pressures, how to address them, and what they mean not just for voting behavior but also for some of the more problematic behaviors associated with men and masculinity.

This article has been updated to include demographic information about the sample studied.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.