Human activities have profoundly shaped the ecosystems of Earth, often with devastating consequences for biodiversity. Among the most significant impacts has been the overhunting and exploitation of animal species for food, leading to the extinction of many. This article explores some of the species humans have consumed to extinction, examining the causes and broader implications of these losses.

The Dodo

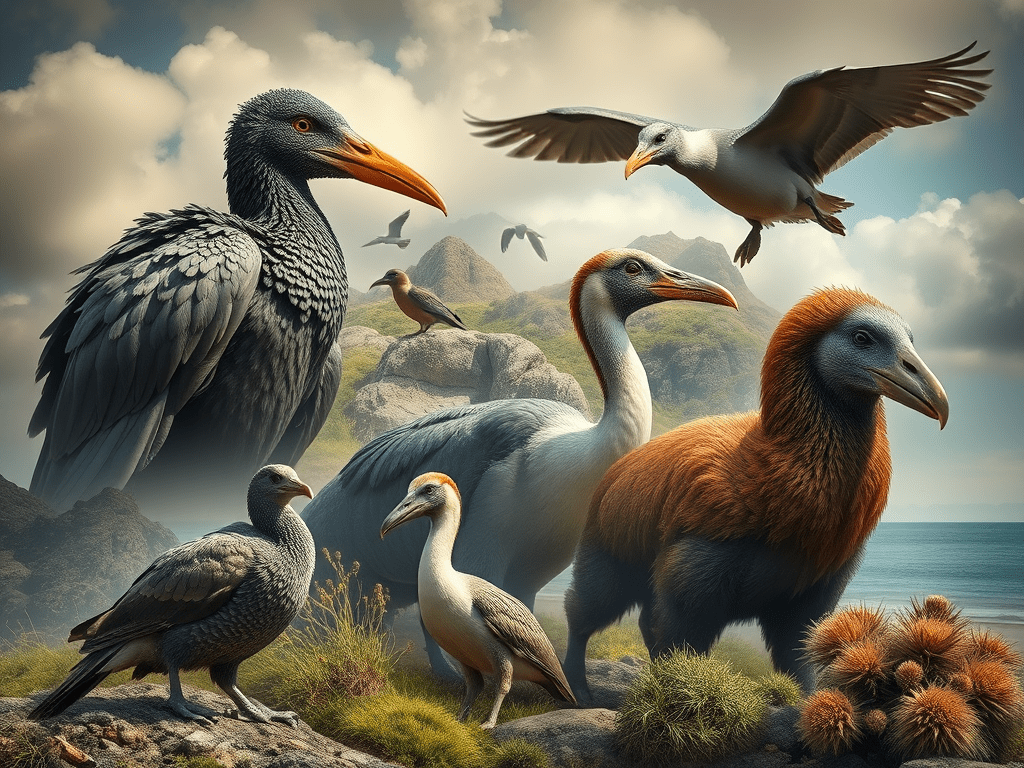

The dodo, a flightless bird native to Mauritius, was discovered by European sailors in the late 1500s. As an island species with no natural predators, the dodo exhibited no fear of humans, making it exceptionally easy to hunt. The bird’s meat was a convenient food source for sailors, while invasive species such as rats and pigs brought to the island destroyed dodo nests, further decimating the population.

Within less than a century of its discovery, the dodo was extinct. Its demise has since become a symbol of the fragility of isolated ecosystems and the consequences of human exploitation.

Passenger Pigeon

The passenger pigeon, once numbering in the billions, was a defining species of North America. Its enormous flocks darkened skies for hours or even days as they migrated. Despite their abundance, passenger pigeons fell victim to relentless hunting during the 19th century. Their meat became a staple for impoverished communities, and commercial hunters killed them in vast numbers to meet the demand.

The destruction of forests, which served as the pigeons’ breeding grounds, compounded the problem. By the early 1900s, the population had dwindled to a few individuals, with the last known bird, named Martha, dying in captivity in 1914.

Great Auk

The great auk, a flightless seabird, once inhabited the North Atlantic coasts from Iceland to Newfoundland. It was hunted extensively for its meat, feathers, and oil. Unlike many other birds, the great auk’s inability to fly made it particularly vulnerable to hunters.

As populations declined, collectors sought out the last remaining specimens for museums and private collections, further hastening the species’ extinction. By 1844, the great auk was gone, leaving behind a cautionary tale of overexploitation.

Steller’s Sea Cow

Steller’s sea cow, a massive marine mammal, lived in the icy waters of the Bering Sea. Discovered by Europeans in the mid-18th century, it was hunted for its meat and blubber, which provided a valuable source of sustenance for sailors and settlers. The slow reproduction rate of the species made it particularly susceptible to overhunting.

Within just 27 years of its discovery, the species was extinct. Its disappearance underscores the speed at which human activities can obliterate even large and seemingly robust populations.

Moa

The moa were a group of large, flightless birds native to New Zealand. They were hunted to extinction by the Māori, who arrived on the islands around 1300 CE. As a primary food source, moas were systematically hunted, and their eggs collected, leading to their rapid decline.

The extinction of moas also had a cascading effect on the ecosystem. The Haast’s eagle, which preyed on moas, lost its main food source and soon followed the moa into extinction. The loss of these species highlights the interconnectedness of ecosystems and the consequences of removing keystone species.

Caribbean Monk Seal

The Caribbean monk seal was once abundant throughout the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico. European colonists and sailors hunted the seals for their meat, oil, and skins. Habitat destruction and competition with fisheries for food further reduced their numbers.

By the early 20th century, sightings of the Caribbean monk seal became increasingly rare, and the species was declared extinct in 1952. Its disappearance serves as a reminder of the impact of unregulated hunting and habitat degradation.

Pinta Island Tortoise

The Pinta Island tortoise, a subspecies of the Galápagos giant tortoise, was driven to extinction by human activities. Sailors and settlers hunted the tortoises for their meat and transported them on ships as a source of fresh food, significantly reducing their populations.

The introduction of invasive species, such as goats, further degraded the tortoises’ habitat. The last known individual, “Lonesome George,” died in captivity in 2012, marking the end of this subspecies.

Cultural and Ecological Implications

The extinction of these species had profound cultural and ecological consequences. Many were integral to the ecosystems they inhabited, playing roles as predators, prey, or ecosystem engineers. Their loss often disrupted these systems, leading to further declines in biodiversity.

From a cultural perspective, the disappearance of iconic species like the dodo and passenger pigeon represents a loss of natural heritage. These extinctions have sparked movements to conserve endangered species and protect ecosystems, yet the lessons learned from these events are sometimes slow to translate into action.

Modern-Day Parallels

While the species discussed are historical examples, many modern species face similar threats. Overfishing, bushmeat hunting, and habitat destruction continue to endanger numerous animals. Species such as the pangolin, vaquita, and several shark species are on the brink of extinction due to human consumption.

The parallels between past and present extinctions highlight the need for sustainable practices and stricter conservation measures. Without action, history may repeat itself, with more species joining the ranks of those lost to human exploitation.

Summary

The history of human-driven extinctions underscores the profound impact our species can have on the natural world. From the dodo to the passenger pigeon, these animals were not only food sources but also integral parts of their ecosystems. Their loss serves as both a warning and a call to action. By reflecting on the past and adopting sustainable practices, humanity has the opportunity to prevent further losses and ensure a more balanced coexistence with the natural world.