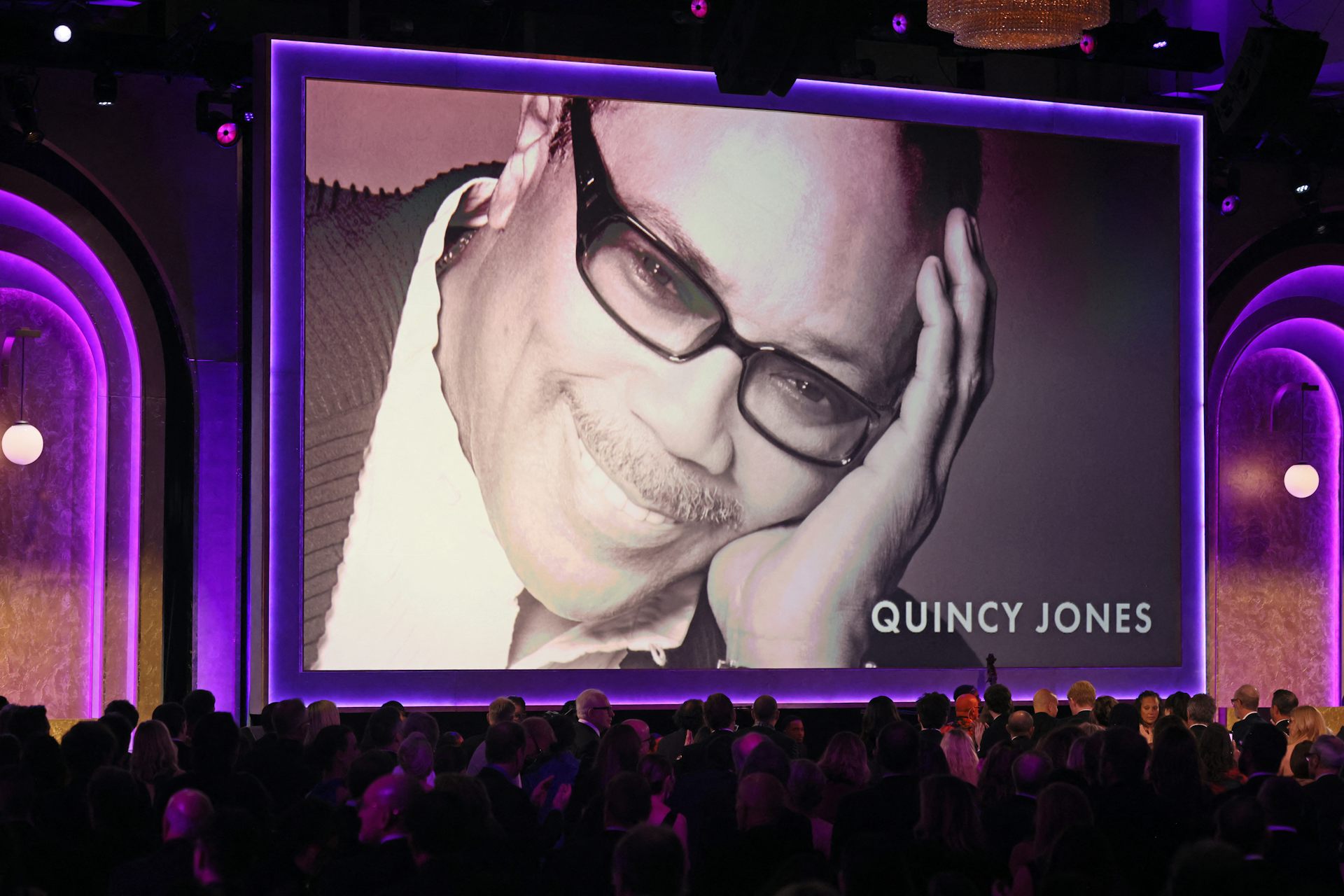

Quincy Jones, who died on Nov. 3, 2024, at the age of 91, was one of the most influential musicians in U.S. history.

You might think such a notable figure would factor prominently in American music classrooms. Yet my research shows that Jones, who was Black, is rarely mentioned in mainstream U.S. music curricula.

As a Black music professor, I believe his absence reflects the fact that music education in the U.S. is still segregated along racial lines, just like the country was for much of its history.

In 2020, music theorist Megan Lyons and I analyzed the seven most common undergraduate music theory textbooks used in the U.S. We found that only 49 of the nearly 3,000 musical examples they cited were written by composers who were not white.

Quincy Jones, the man and the music

A composer, arranger, performer and producer, Jones was a musician whose influence on American music is hard to overstate. He won 28 Grammy Awards, wrote multiple film scores and was intimately involved in some of the most important musical developments in America in the mid-to-late 20th century, such as the rise of the jazz artist as pop music arranger. He produced the world’s best-selling album of all time, Michael Jackson’s “Thriller.”

Jones was a trumpeter who began his career playing with bandleader Lionel Hampton in 1953, but he soon branched off to become much more than a sideman.

Early on, he performed with legends such as Count Basie, Dizzy Gillespie, Elvis Presley and Frank Sinatra, and he produced and arranged music for vocal titans such as Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan and Diana Ross. His pivot to pop music in the late 1970s helped usher in a revolution of funk, disco and early hip-hop.

I see Jones as an essential piece in the history of American music. Yet he’s absent from the music classroom, as are so many Black artists throughout history.

This absence is leading more music educators to recognize what my research also finds: American music education remains deeply rooted in an ideology that has dominated U.S. history – white supremacy.

Segregation in music

One of the most important linchpins of American white supremacy was racial segregation – that is, keeping white people and Black people apart. This racial segregation has been evident in music education, too, throughout American history.

Take, for example, the fact that the majority of composers who are studied in American music institutions such as the Eastman School of Music and the Juilliard School, along with most major university music departments, come from a Western musical tradition and are not American. I’m referring to Johann Sebastian Bach, Ludwig van Beethoven, Frédéric Chopin and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, among a handful of other revered figures. These are all white, European men who died long ago.

This is one reason why students pursuing a bachelor’s degree in jazz studies generally take classes entirely outside of the generic category of “music major.” Courses on jazz, a genre deeply rooted in African American musical traditions, frequently do not count as core classes for the music major at many U.S. colleges, conservatories and universities; classical music classes do.

And in a contemporary twist on musical racial segregation, classical voice and instrumental students in at least one college are warned by their studio teachers not to sing or play genres associated with Blackness such as jazz, gospel, blues or hip-hop for fear that those styles will negatively influence their classical approach.

From the moment the U.S. Supreme Court made racial segregation unconstitutional in its landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka ruling, white America has fashioned new ways to keep races apart.

In music, this has manifested itself in keeping curricula segregated.

If you’re thinking that all pop musicians like Jones are banned in the music classroom, just Google “the Beatles in music curricula.” There are countless college courses. The Beatles have been commonly studied for over 20 years.

The Beatles weren’t even American, but they’re part of the American music curricula. And they were white.

Integrating music curricula

“American music academies,” as I’ve previously written in The Conversation, “generally reflect the social norms of the day.”

And social norms around race and racism are changing fast in the U.S., affecting an array of industries, from fashion to finance.

So what might a relevant American music curriculum look like?

I’d begin by introducing students to the first great American musician, Francis “Frank” Johnson. Born in 1792, Johnson was a prolific composer, violinist and band leader whose life and work are rarely studied in the U.S. He’s not to be confused with Frank Johnson, born in 1789, another notable early American violinist and brass ensemble leader.

I’d continue with other significant 19th-century figures such as New Orleans pianist Basile Barès, whose music filled American dance halls after the Civil War. Or Edmond Dédé, who studied and lived in Paris, France, for years before returning to his native New Orleans.

I’d focus their attention on the Broadway composer Will Marion Cook, who studied violin at Oberlin College as a teen and later with acclaimed virtuoso Joseph Joachim in Berlin, Germany. Or on the conductor, composer and librettist Harry Lawrence Freeman, whose 21 operas remain remarkably underexplored.

And I’d never let my syllabus skip the vocal music of Margaret Bonds, the symphonic works of Julia Perry, the atonal music of Undine Smith Moore or the music theories of Roland Wiggins.

Though I’ve only scratched the surface, all of these musicians were African American – and I didn’t even mention any blues, hip-hop, Motown, rock or R&B artists.

In my opinion, Black music and musical genres have had a greater impact on the course of American music than any other style or genre. For this reason, I believe universities and music schools should integrate this music into their music curricula – and feature it prominently and proudly.

From Francis Johnson to Quincy Jones, Black music exemplifies the musical greatness the U.S. is capable of producing, for Americans and for the world.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.